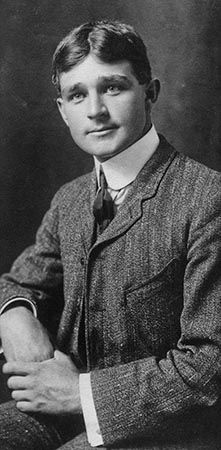

Fairmont's most famous writer was born July 27, 1908 on his maternal grandfather's farm in the Iona community. His mother, Elizabeth Parker Mitchell, had returned to her parents' home because his father, Averette Nance Mitchell, was hospitalized with some sort of contagious fever that was spreading at the time. A. N. and "Miss Betty" moved into Fairmont later that year when their house on Church street was built.

Joseph grew up as a normal child with his expanding family. Brother Jack was born in 1911, sister Elizabeth in 1913, Linda in 1915, Harry in 1919 and Laura in 1922. He attended Fairmont School which was a block from his home, and after school spent his free time exploring Pitman Mill Branch, which flowed through A. N.'s property behind the house. There he developed his love of nature and could easily identify the native vegetation and wildlife.

His mother, herself an educated woman, made certain that Joseph and his siblings had ample reading materials available at home so early in life he developed the reading habit that remained with him for the rest of his life. He was a good student in everything but mathematics, developing an aversion to it that also followed him throughout life. In high school he did well enough to pass but upon enrolling at UNC in Chapel Hill he had to confront his mathematics block.

Fairmont High School graduating class, 1925; Joseph Mitchell, 3rd row, 3rd from left. Robert Floyd family archive, used with permission.

Joseph somehow convinced the dean of the school of liberal arts to allow him to remain in school. Despite knowing he could never graduate without the requisite math courses, Joseph took a full spectrum of English, journalism, art and geology courses and left the university without a degree in 1929. While there, however, he began to write in earnest, submitting Sunday features to the largest state newspapers. He also wrote fiction, publishing several stories in the regional literary magazines of the day. He was also Associate Editor of The Carolina Magazine. Writing, he decided, was what he wanted to do.

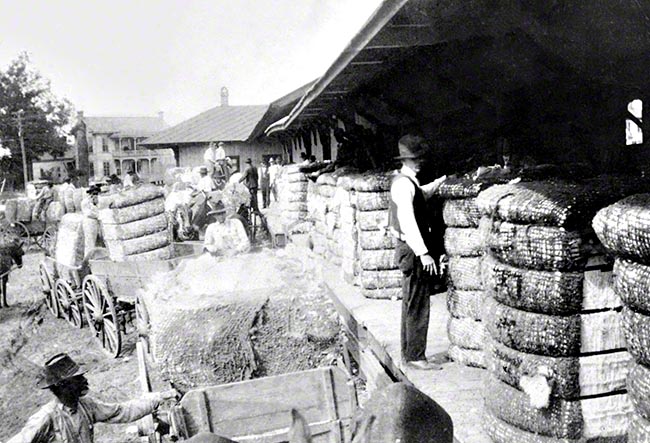

He submitted a piece titled "Tobacco Market" to the New York Herald Tribune in the summer of 1929. It ran on Sunday, October 13, 1929, giving him his first byline in one of the best papers in New York. Deciding that New York was where he wanted to be, he convinced A. N. to take him the 40 miles to Fayetteville to catch a train to the big city and begin his career as a writer. He was hired by the New York World as a copy boy just after the stock market crash of 1929.

In early 1930 he was hired by the Herald Tribune as a "district man", his first district being Harlem. Six months later he was promoted to reporter, handling all assigned tasks with speed and skill. With a brief interruption as a deck hand on a tramp steamer, he would ply his craft for the rest of his life.

Meeting and marrying Therese Jacobson, he put down roots in the city. While returning often to Fairmont, he was to remain in New York City. Moving to the New York World, he began writing the type of profile pieces that characterized his career. He was prolific and had wide-ranging interests.

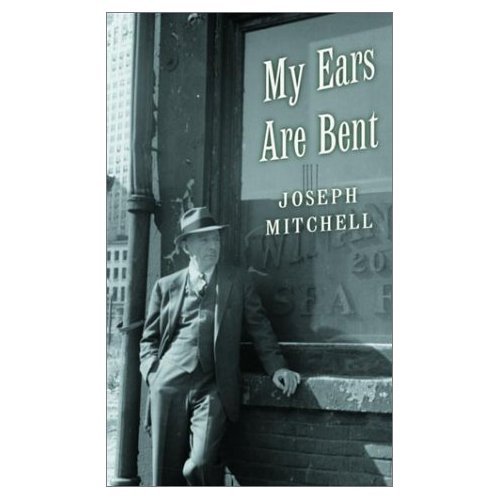

Mitchell moved to the New York World-Telegram. For more than three years he wrote non-stop for the paper and, in 1934, he was assigned to the team of reporters who would cover the Lindberg Kidnapper murder trial. During the trial, he was approached by an editor or The New Yorker magazine about perhaps coming to work there. He talked back and forth with several staff there, finally starting to work on September 26, 1938. This was about the time that he published "My Ears are Bent", a collection of his best newspaper columns, which was well received by critics.

While working for almost sixty years at The New Yorker, Mitchell became famous for his profiles and for his Reporter-at-Large pieces. Some of his articles were turned into books. "McSorley's Wonderful Saloon" began as a piece about the famous ale house and became a book published in 1943. "Old Mr. Flood" (1948) began as a profile about a man who hung out at the Fulton Fish Market. It was written to be biographical, but was actually a composite of several men that Mitchell knew.

Thus began a controversy with Mitchell regarding whether or not he just "made it all up." This would not become widely known until the end of his career, but has been discussed since his death by admirers and critics alike.

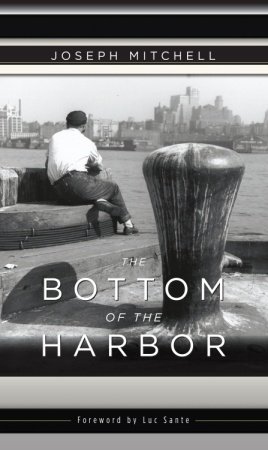

"The Bottom of the Harbor" (1960) reported on the pollution of New York harbor, describing what was happening to the marine life of the harbor. Joe, a connoisseur of shellfish served up in the Fulton Fish Market, was horrified.

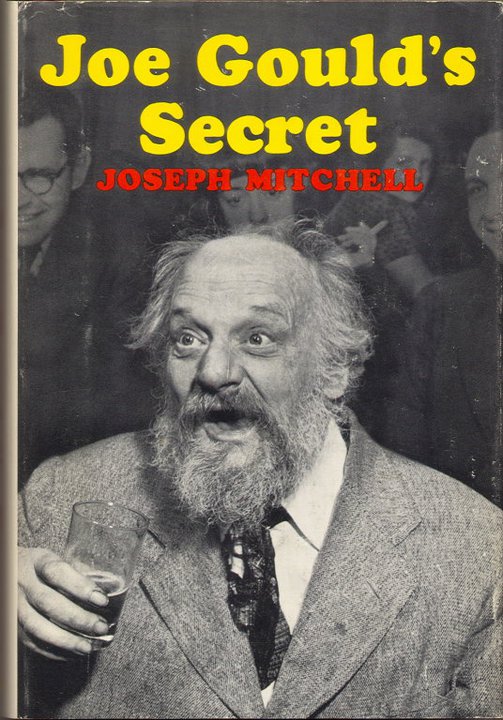

"Joe Gould's Secret" (1965) started out as a profile in The New Yorker entitled Professor Sea Gull. Mitchell pulled it up twenty years later, expanded on it and it became a book. Joe Gould was an actual person who lived in Greenwich Village. He was Harvard educated but sponged off of his rich friends. He was writing "An Oral History of Our Time", which intrigued Joe enough to continue his involvement with Gould for more than ten years after Professor Sea Gull was published. I won't give the plot away, but this book is widely regarded as Mitchell's finest.

It was also his last published writing. For more than three decades he went to the office each day, closed the door and began typing. Nothing was ever published. About three chapters of an autobiography were found after his death, some of which was published in the New Yorker in 2012.

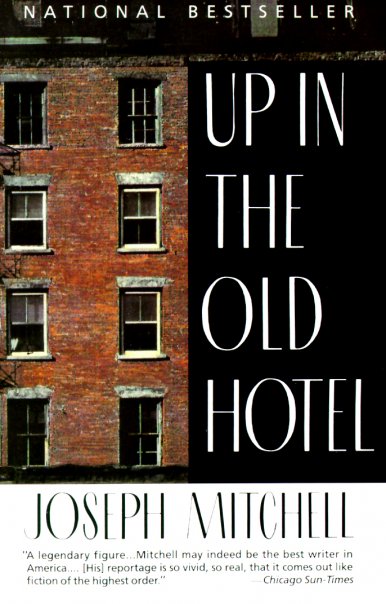

All book covers courtesy Joseph Mitchell - Facebook page

His lone remaining literary contribution was to publish "Up in the Old Hotel" (1992), an anthology of his work. Joseph Mitchell died on May 27, 1996 of cancer. He is buried in Floyd Memorial Cemetery in Fairmont.

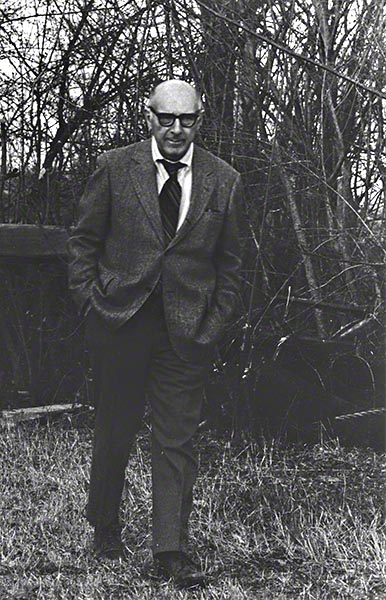

Joseph Mitchell, at home on his farm in Fairmont. Photo credit: James L. Pate, Jr., used with permission.